Jesus called… (Matt 4.21)

“Come, follow me,” Jesus said… (Matt 4.19)

Jesus had finished instructing his twelve (Matt 11:1)

Jesus got up and went with him, and so did his disciples. (Matt 9.19)

Jesus sent out with the following instructions (Matt 10.5)

Jesus told them another parable. (Matt 13.10 & 24)

…and his disciples followed… (Matt 8.23)

“Follow me,” he told him (Matt 9.9)

Jesus called, said to follow, instructed, told parables, and sent ahead.

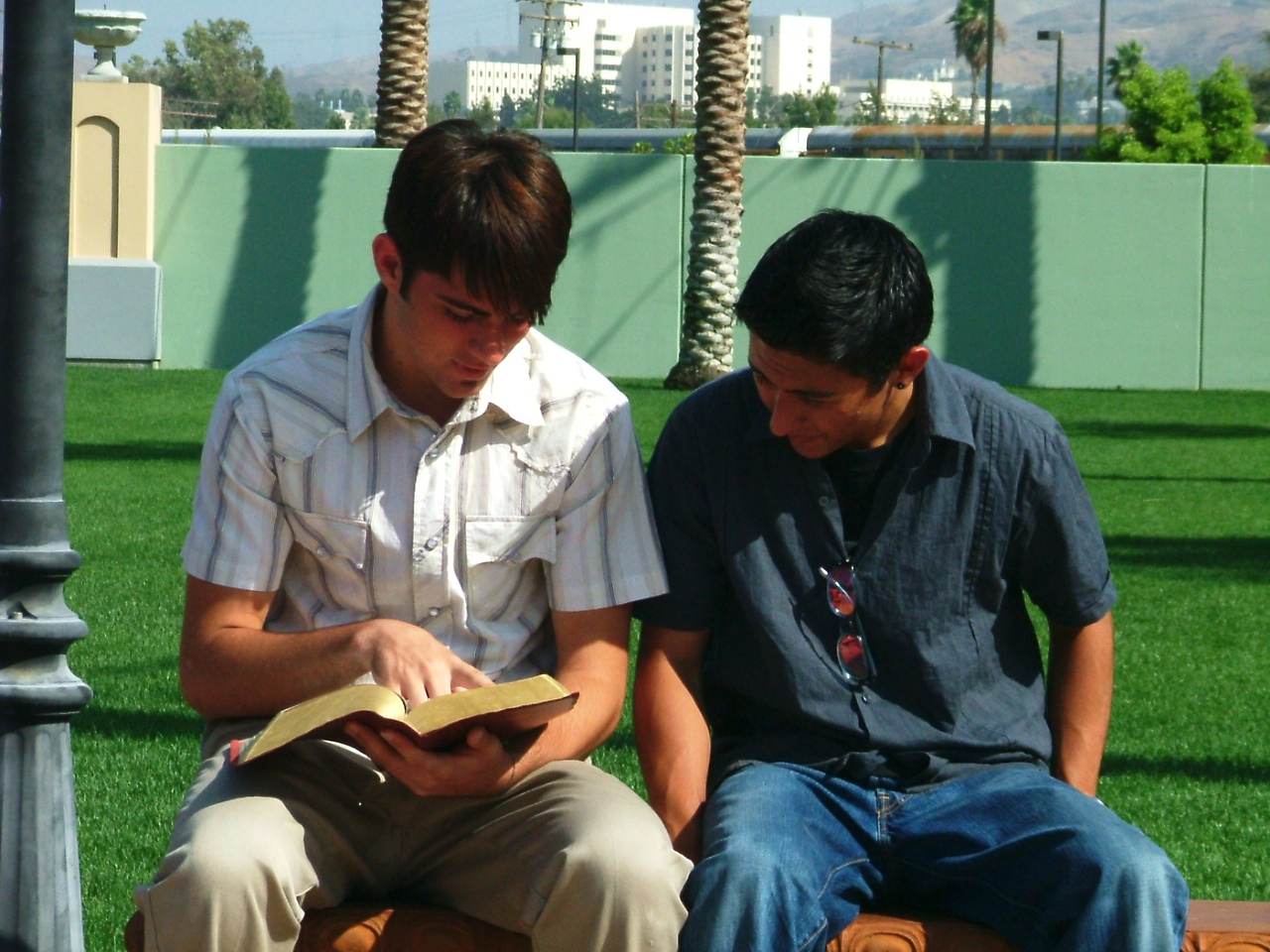

A Tale of Two Youth Leaders

Jason was a new volunteer at First Lutheran Church. He joined the church two months ago after moving into the area, and Pastor Ray noticed right away that youth were attracted to his energy and humor. Now it was Jason’s job to help a fledgling youth ministry exist at First Lutheran. He wasn’t sure where to start.

After a few months, Jason called the pastor because some of the youth had gotten into playing online games that seemed satanic. He was looking for advice. Pastor Ray told Jason that he preferred a hands off approach to ministry, but he would support Jason in whatever decisions he made.

In another state, Deana began working as a youth ministry volunteer. She had a very poor experience (in her own mind) at her last church, but wanted to support youth in her community. Pastor Dan noticed right away that youth were attracted to her energy and humor.

STOP

Notice that the beginning of Deana’s story sounds almost the same as Jason’s. Imagine, however, that Pastor Dan takes on the role of mentoring his future leader the way that Jesus mentored and molded his disciples — his future leaders. Imagine … what would it look like?

START

Pastor Dan was going to visit a family one afternoon and he called Deanna to see if she could squeeze a little time away from work and join him. Thankfully, Deana had that kind of flexibility and jumped at the chance. Afterward Dan and Deana grabbed a cup of coffee to talk about her experience. After he listened to Deana’s story from her last church, Dan shared a few stories of some of his more awkward ministry moments.

After a few months, Deana had followed Pastor Dan through many other experiences and been taught some of the legal issues of Youth Ministry (including background checks), she was encouraged to begin to look for a few girls that she would begin to mentor in the faith. She told Pastor Dan that she did not know how to mentor. Dan chuckled and said that she did know — it was what she had been experiencing with him over the last few months. He added that one of the more important aspects of mentoring is to send out your “student” to mentor someone else.

Deana became very anxious at this point in the conversation and made it known to Pastor Dan. She did not think she was ready to go out on her own and mentor young girls. Dan smiled at her determination and let her know that being sent out did not mean he would not be there to mentor her further. A good mentor always stays in touch, he said.

Deana put her foot down. She demanded that Dan not use a hands off approach. Thankfully, Pastor Dan was a wise leader and understood that the hands off approach was detrimental to ministry … but so was a micromanagement style of leadership.

Mentors Make Mentors

All true discipleship leads to mission. If it does not result in mission then it is not discipleship. Mentorship is discipleship. The ancient church’s way of discipling was a mentorship process attached to mission. In essence, mentors made mentors. Disciples became the teachers of more disciples.

Every successful leader has had a good mentor. I appreciate an old quote from a very old book that explains the essence of a good mentor. “[Transforming leadership] occurs when one or more persons engage with others in such a way that leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality…. Transforming leadership is dynamic leadership in the sense that the leaders throw themselves into a relationship with followers who will feel ‘elevated’ by it and often become more active themselves, thereby creating new cadres of leaders” (Peters & Waterman, In Search of Excellence p. 83).

Characteristics of Mentoring

Common characteristics of mentoring from a variety of authors and thinkers include:

Choosing Well

Mentors should hand pick their apprentices, or protégés.1 Choosing the protégé well is essential to the success of the relationship. They speak of spotting raw talent.2 Also, based on values and common goals there should be an identifying and matching of mentoring participants.3

Commitment to the Relationship

Building a good relationship is important as well. Creating a solid foundation for a trustworthy relationship will take time and commitment. Mentors in particular, are warned to be aware of the commitment and not to overextend themselves to the point of becoming a poor mentor.

Self Awareness

Therefore a mentor needs to be self aware. Self-knowledge keeps the mentor aware of personal issues they bring into the relationship.4 One author uses the phrase, “Knowing thyself as a mentor.”5

Honesty in Adversity

Honesty is a part of knowing oneself as a mentor and also important to maintaining a trusting relationship. A mentor needs to make a practice of telling the truth even in uncomfortable situations so the protégé can make accurate personal assessments.6 He needs to value difficult situations as a part of the process and continue forward through adversity.7

Humility as a Role Model

The mentor is not the dominator in the relationship. She is not a “sage on the stage” and must practice humility.8 She is a role model and should work intentionally at this.9 Mentoring is a process that begins with the heart. Within this modeling process the skills and attitudes are more easily “caught than taught.”10

Seeing the Art Within

In Tacit Knowing Truthful Knowing, Michael Polanyi talks about tacit knowledge as being a knowledge that is hard to put into words. He refers to the concept of seeing a statue within the stone. The skill of the mentor when advocating and supporting a protégé or apprentice, needs to be one of seeing the art within the apprentice and seeking to bring it to light.11

Bold and Reflective

As a mentor, creating experiential pedagogy requires being bold. A mentor does not skirt the issues and does not fall back on modernist lecture methods. As Sullivan contends in How to Mentor in the Midst of Change, “Making meaning is its own challenge. Reflection on one’s work results in improvement and in a clearer sense of purpose . . . to think through probing questions, to keep journals, to protect some time each day for thought rather than action. These solitary approaches to reflection become greatly enhanced when one shares thoughts, feelings, and ideas with another person.”12 The mentor relationship is that place for bold reflection and sharing.

Control of Process

The apprentice is in control of the process. The protégé is responsible for the purpose of the relationship as well as the goal setting.13

Evaluation and Re-negotiation

When the goals have been met or changed there needs to be a re-negotiation of the process. This will come through evaluation of results and proposals; and then a revision based on data and recommendations.14

Closure

There needs to be an agreement made on how to bring closure to the process.15 Sometimes this may mean ending the commitment before the goals have been met due to a change in circumstances.16 The key is to find helpful ways to say goodbye.17

Conclusion

Jason and Deana would both benefit from a solid organic mentoring process. Pastor Dan understood and valued this relationship with Deana. Organic mentoring depicts a mutual relationship that is developing, dynamic, adaptable, encourages steady change (as opposed to instant change), and allows for interdependency of those involved.

1W. Brad Johnson and Charles R. Ridley, The Elements of Mentoring, 1st ed. (

New York, N.Y.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 4.

Chicago,

Ill.:Dearborn Trade Publishing, 2004), Introduction.

3Cheryl Granade Sullivan, How to

Mentor in the Midst of Change, 2nd ed. (

Alexandria,

Va.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2004), 18-19.

4David Clutterbuck, Techniques for Coaching and Mentoring, 1st ed. (

Boston,

Mass.: Elsevier, 2004), 2.

5W. Brad Johnson and Charles R. Ridley, The Elements of Mentoring, 1st ed. (

New York,

N.Y.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 4.

6Ibid.

7David A. Stoddard and Robert Tamasy, The Heart of Mentoring: Ten Proven Principles for Developing People to Their Fullest Potential (

Colorado Springs,

Colo.: NavPress, 2003). And also, Stone.

8Johnson and Ridley, 4.

9Ibid.

10Stoddard and Tamasy, Introduction

11Michael Polanyi, Tacit Knowing Truthful Knowing: The Life and Thought of Michael Polanyi (

Quinque,

Va.: Mars Hill Audio), Cassette Tapes.

12Sullivan, 4-5.

13Ibid., 18.

14Ibid., 19.

15Lois J. Zachary, The

Mentor’s Guide: Facilitating Effective Learning Relationships, 1st ed., The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series (

San Francisco,

Calif.: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2000), 52.

16Clutterbuck, 3

17Johnson and Ridley, 4.

0 Comments